At the Heart of Transportation: A Moving History

Table of

Contents

June 2017

This overview of the Canadian Transportation Agency’s history was first released on the occasion of the Agency’s centenary in 2004.

This updated version has been prepared to mark Canada’s 150th anniversary. The Agency has played an integral role in helping to foster a competitive, efficient, accessible national transportation system and looks forward to continuing to do so for many years to come.

Scott Streiner

Chair and Chief Executive Officer

All Aboard

The Board of Railway Commissioners, 1904 to 1938

- February 1, 1904, the Board of Railway Commissioners was inaugurated.

- August 4, 1914, Canada joins Britain in the war effort.

- 1930s, the Great Depression hits—many Canadians experience difficult times.

The Canadian Transportation Agency had its origins over 100 years ago in an atmosphere of intense commercial competition. It has emerged as a vital though largely low-key player in shaping the Canada we know today.

The Agency’s story began with the establishment of the Board of Railway Commissioners in Ottawa on a snowbound February day in 1904.

From the beginning, the Railway Commissioners faced obstacles. According to the Railway Act of 1903, the Board was to be inaugurated on February 1, 1904. However, as the Ottawa Citizen noted on February 2, in a procedural glitch, the appointments to the Board had been made “by Order in Council and gazetted before the date of the coming into force of the Act which established the commission.” The official launch would be delayed because “new Orders in Council will have to be passed making the appointments.”

Even Nature conspired against the new Board. Local newspapers ran stories about the record snowfall in the Dominion’s capital that February, making it difficult to travel. “Snow clearing seems to be the principal industry in Ottawa this winter,” the Citizen glibly reported.

It was not an auspicious beginning, but the newly appointed Railway Commissioners plunged ahead. On February 9, Andrew G. Blair, as chairman of the Board, addressed a group of railway executives and business luminaries. He was an imposing figure, a large, dour-looking man, a month short of his 60th birthday, his face, beneath a heavy white beard, worn by the tense months of political fighting, and then, lately, by inertia.

But his voice did not waver when he spoke: “The powers and jurisdiction conferred upon this Board are comprehensive in their scope, far-reaching in their effects and they will touch at a vital point the already immense and constantly increasing business interests of the country on the one hand, and the great and always growing interests of the railway interests on the other.”

Moments later, however, he added, “We are without a staff and without quarters to transact our business […] Although we are quite unequipped, we thought we would take up two or three applications at this date.”Footnote 1 If his comments verged on whining, he could be forgiven. Blair had been working toward this goal for several years and was anxious to see it accomplished.

As far back as 1896, he had seen the necessity of establishing a permanent and independent regulatory body to ensure that the public interest was served in the race to expand Canada’s railways.Footnote 2

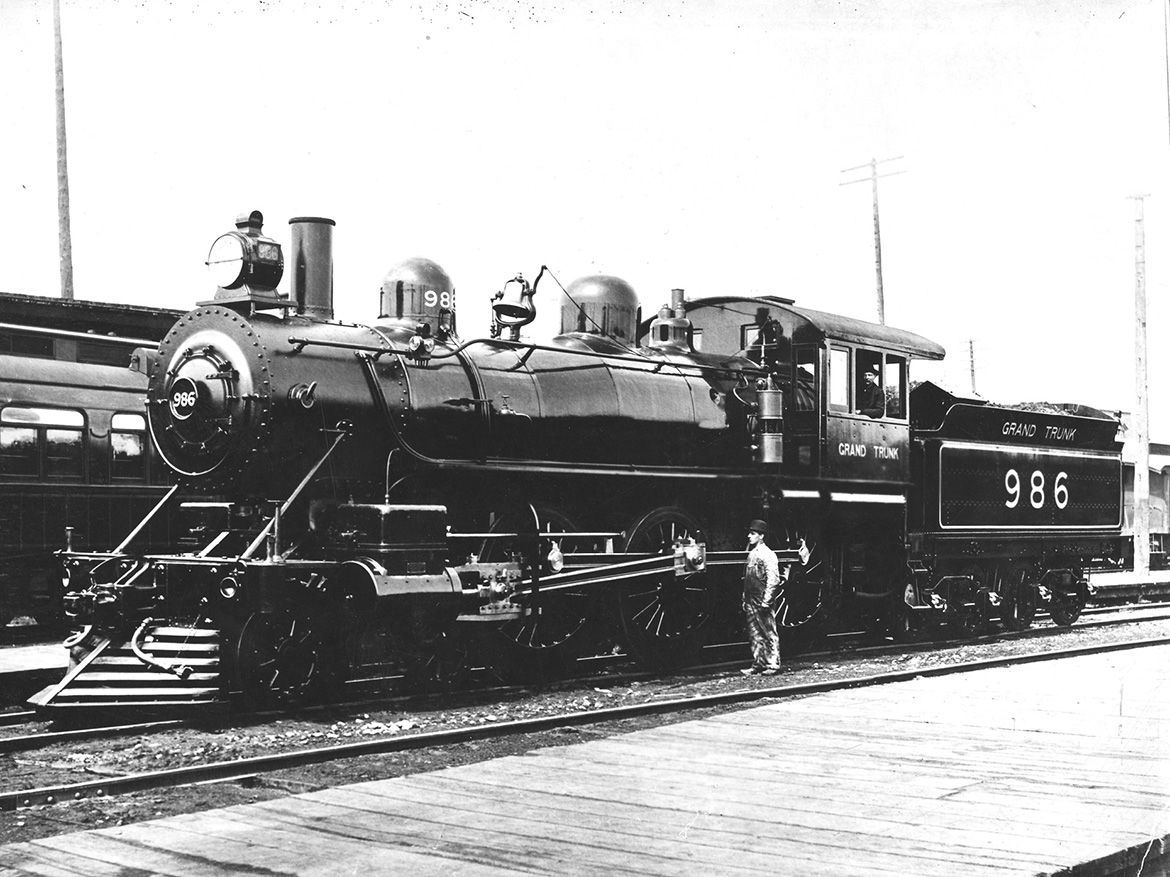

Railway companies had been at the centre of economic growth in Canada since the 1850s. In fact, they had played a dramatic role in the creation of Canada. The Grand Trunk Railway, completed between Toronto and Montréal in 1856, linked Canada West with Canada East (now Ontario and Québec), and helped to lay the groundwork for Confederation.Footnote 3

The promise of a railway was instrumental in the decision of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to join as well. (The Intercolonial Railway was completed in 1876, linking Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to Québec.) In 1871, British Columbia was drawn into Confederation with the promise of a rail link to the rest of Canada. The result of that provision was Canada’s first transcontinental railway, completed in 1885 by Canadian Pacific Railways (CP). Aid for Prince Edward Island’s debt-ridden railway, and a year-round link to the mainland, lured that province into the union in 1873.

At the dawn of the 20th century, shiploads of immigrants were pouring into the country’s ports, and the railways, with their huge land grants, were largely responsible for where they settled. Railway companies also controlled the movement of goods and passengers across the country, and were vital to the Dominion’s industrial growth.

But as Canada’s business interests became more dependent on rail travel for supplies and markets, shippers began to complain about freight prices and about the railways’ near monopolies on transportation. Railway companies argued that they needed to charge rates that would pay their costs, which indeed they did. But they were not charging everyone the same rate, and that was the crux of the problem.Footnote 4

Freight-rate competition was healthy in Central Canada, where several railway companies vied with one another, with water transportation and with American railway companies south of the border for customers. The railway companies had to set competitively low rates, often offering special deals to their bigger and better customers.

But in regions where competition was low or non-existent, freight rates were set higher. The railway companies reasoned that they were recouping the profits that they had shaved off in the more competitive regions. It made good business sense to them, but not to the shippers being charged the higher rates. Inevitably the complaints were heard by the politicians in Ottawa.

Some of the loudest complaints came from the western provinces where the only transcontinental railway, CP, had held a virtual monopoly since 1885. Successive governments in Ottawa, which had heavily subsidized much of the railway construction across Canada, sought a solution to the debate.

When Andrew G. Blair became Canada’s Minister of Railways and Canals in 1896, there was already a Railway Committee of the Privy Council, of which he became chairman. The Committee had been created by the Railway Act of 1888. (This Act was a revision of the General Railway Act of Canada of 1868, the first railway legislation after Confederation, which itself was drawn from the Railway Clauses Consolidation Act of 1851. Neither of these acts had any real force, and the railway companies had largely ignored them and set their own rates.)Footnote 5

The Railway Committee of the Privy Council was intended to regulate railway freight rates and to hear complaints as a judicial body. But Blair soon discovered that it had serious defects: it was made up of politicians who could not be called unbiased; it was based in Ottawa and did not travel; committee members did not have any technical training; and there was no permanent staff.

A lawyer and a seasoned politician, Blair was known for his canny political mind and his unwavering determination. He had sat for 18 years in the New Brunswick legislature, 14 years of that time as premier. When he joined Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s government, he was 52 years old. He brought with him to Ottawa his wife, Anne, a welcome addition to the capital’s social circle, and those of his ten children who were still living at home.Footnote 6

As Minister of Railways and Canals, he set to work to find solutions to the freight-rates problem. In 1897, Blair worked on the Crowsnest Pass Agreement in which the government gave CP a subsidy for construction of its Crowsnest Pass line in return for the company reducing rates — the so-called Crow rate — on grain going to the Lakehead and to many westbound routes.

Grand Trunk Railway “Ten Wheeler” steam locomotive No. 986, 1900, CSTM/CN003833

In 1899, Blair commissioned Simon J. McLean, a noted political economist of the time, to study railway commissions in Britain and the United States, and then, in 1901, to examine railway rates in Canada. With the results of McLean’s two reports, Blair introduced a bill in 1902 to establish a railway board. That bill was rejected, so Blair went back to work to draft another proposal.Footnote 7

On March 20, 1903, he introduced a revised bill to establish a Board of Railway Commissioners, an independent body with regulatory powers over railways. That bill passed, and with the Governor General’s assent on October 24, 1903, it would become law.

Meanwhile, the government was considering another solution to the freight rates issue — competition. And Sir Wilfrid Laurier had taken the matter into his own hands. Two railway companies had been lobbying for several months for government funds to expand their lines in the West.

Laurier held the view that, with competition, CP would lower freight rates, western shippers would be happy, and the competing railway companies would flourish. He also had visions of the grain-rich West expanding with new settlers and new industry. He reasoned that a second railway company would be needed to accommodate this burgeoning wealth.

The Grand Trunk Railway — with lines within Central Canada that reached from North Bay, Ontario in the north, to Chicago in the U.S. Midwest, and to Portland, Maine in the East — proposed, with government support, to build a western system from its northern terminus at North Bay to Winnipeg, and on to the West Coast. Promoters of the Canadian Northern Railway (CN), with links from Edmonton to Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay), proposed branches extending east and west to both coasts. At first, Laurier attempted to work out a deal in which the two railway companies would combine their efforts into one transcontinental network, but an agreement could not be reached.Footnote 8

Laurier remained determined to have a second transcontinental railway. He favoured the Grand Trunk and proposed a deal in which the government would build the eastern section of the new line and the Grand Trunk would build the western portion.

Blair objected, chiefly because the Grand Trunk already had an eastern terminus at Portland, Maine, completely bypassing the Maritime provinces. Blair had his own proposal — the Canadian Northern, with an extension to the West Coast, would hook up with the government-owned Intercolonial at Québec City, which would take traffic through the Maritimes to Halifax.

Laurier would not be deflected from his own developing plan. Blair would not support him. In the resulting impasse, Laurier decided to ignore Blair, excluding him from the railway discussions. On July 13, 1903, Blair resigned as Minister of Railways and Canals.

On July 30, Laurier presented his bill giving the go-ahead for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. Blair stood as a private member in the House of Commons on August 11, 1903, to deliver a speech condemning the Grand Trunk plan. It was a stirring bit of rhetoric, but it had little effect on the plan. On September 29, the bill passed its third reading.

In December, Laurier appointed Blair to head the new Board of Railway Commissioners. The two men had not resolved their differences, but the veteran politicians had made expedient choices. Laurier saw that Blair’s proven abilities would be put to good use as chairman of the new Board, and appreciated the advantage of removing him from the House of Commons where he could cause trouble.

Blair, for his part, had failed to stop the Grand Trunk bill and was short of allies in the House. The task of leading the new Board, his brainchild, through its first faltering steps was an opportune route for retreat. And so there he sat on that frosty February day in 1904, in an office he had known well as a cabinet minister. The Board had been given temporary quarters in the Railway Committee’s old offices, in the West Block of the Parliament Buildings.

But, despite the familiar surroundings, Blair had entered a whole new realm, an uncharted course in Canadian regulation. No one could doubt the tremendous authority that had been bestowed on the Board. It had the full powers of a Superior Court to hear all railway complaints and its decisions had the force of law. It had regulatory powers over construction, operation and safety of railways (except those owned by the government), and on such matters as freight rates, fares, demurrage and other charges.

According to the Railway Act, the Board was to consist of three commissioners, each appointed for a ten-year term. Michel E. Bernier, who had been in Laurier’s cabinet as Minister of Inland Revenue and who had sat on the Railway Committee of the Privy Council with Blair, was appointed the Deputy Commissioner. The other member of the Board was James Mills, who had been called from his post as the first president of the Ontario Agricultural College in Guelph, Ontario.

Together the three men set to work to establish rules and regulations for the new body. They had no models to follow. Theirs was the first independent regulatory body established by the Dominion government. They would lay the groundwork for a new method of public regulation in Canada.

The first Annual Report of the Board shows that the commissioners took up their tasks with a great deal of energy. Between February 9 and October 18, the Board held 62 days of public sittings. Although 38 of those days were spent in Ottawa, the Board travelled to Toronto for six days of hearings in June and, between August 8 and September 18, it held 18 days of sittings in 15 different locations between Winnipeg and Victoria.

The Board also hired 19 permanent employees — one of them being Blair’s son and namesake, A.G. Blair Jr., as the Board’s law clerk — and set up four departments to handle routine work.

The Records Department dealt with the paperwork — complaints received by the Board, orders and decisions issued by the Commissioners as well as investigations carried out. The Traffic Department dealt with tariffs and freight classifications. The Engineering Department inspected and approved construction and repairs on railways and crossings. The Accident Branch investigated railway accidents.

The Board was also establishing its credentials with the Canadian public. In July 1904, the Canada Law Journal reported that “we doubt if even the Dominion Government, which constituted the Board, has yet realized that it has created a Court of such extended jurisdiction as this Board possesses, and which jurisdiction, if wisely exercised by a tribunal of competent members, will be both a safeguard to the public and a speedy method of settling differences between railway companies.”

First passenger train to Edmonton from Winnipeg, Canadian Northern Railway Company, 1905, CSTM/CN002380

But the 60-year-old Blair, busy as he was marshalling the Board through its formative days, had not hung up his gloves in the political ring. The fall of 1904 brought the excitement of a federal election and fresh battles to be fought. Laurier led his campaign with promises of a bigger and better Canada.

The election would yield one of the most often repeated — and misquoted — phrases in Canadian political history. On October 15, The Globe newspaper reported on an election rally for Laurier, at Massey Hall in Toronto. “Let me tell you, my fellow countrymen, that all the signs point this way, that the twentieth century shall be the century of Canada and of Canadian development,” Laurier declared. Among Laurier’s promises was the second transcontinental railway that his deal with the Grand Trunk Railway Company would provide.

Four days later, the October 19 edition of the Daily Telegraph in Saint John, New Brunswick carried a blaring headline, “BLAIR RESIGNS AND WILL STUMP COUNTRY AGAINST G.T.P. SCHEME.” According to the Telegraph, Blair had sent the following telegram to its editor: “I authorize the announcement that I have resigned my position as Chairman of the Railway Commission and have notified the Prime Minister that, beyond re-affirming my strong objection to the Grand Trunk Pacific scheme, I have no present intention of re-entering public life.”

Laurier’s deal with the Grand Trunk Railway had stipulated that the Dominion government would build the eastern half of the system, from Winnipeg to Moncton, New Brunswick, to be called the National Transcontinental. After completion, the government would lease that section to the Grand Trunk’s still-to-be-built subsidiary, the Grand Trunk Pacific, which would extend across the Prairies to the port of Prince Rupert in British Columbia. However, Blair, along with many others, raised doubts that the Grand Trunk would use Moncton as its eastern terminus when it already had one in Portland, Maine.

Another story in the Telegraph that day carried Blair’s last address as chairman to the Board of Railway Commissioners. “I feel that this infant child, at whose birth I closely attended, has been nursed by this time into some degree of strength and vigour. What little abilities and energies I possess have been applied in that direction. I think it has now got fairly well on its feet, that it will be able to move along and that it will grow in favour. I believe that this commission will grow in strength and usefulness and come to be regarded as one of the most important and useful institutions in the country.” He also alluded to “prospects” in his future, suggesting that he might have other job opportunities.

Blair’s warning about the Grand Trunk was repeated on October 22 in the Saint John Telegraph: “It is vital that the Government should not only own but operate the railway, because in no other way can you guarantee that the traffic will go through a Canadian outlet. We are spending the money, and we are getting nothing for it.” Blair again trumpeted the advantage of the government-owned Intercolonial Railway system through the Maritimes.

The views expressed by papers varied according to their political alignment, some maintaining that Laurier’s Grand Trunk deal was selling Eastern Canada down the river. The Maritimes fretted that they would be thrust out in the cold if the Grand Trunk project went ahead. Reports speculated that Blair would run as a Member of Parliament, that Laurier’s defeat was imminent. Other papers minimized the impact of Blair’s opposition and even questioned the authenticity of Blair’s telegram that had been quoted in the Saint John Telegraph.

A week earlier, William Mackenzie and Donald Mann, the promoters behind CN, had bought La Presse newspaper in Montréal. A rumoured conspiracy to turn La Presse into a weapon against Laurier sent the Prime Minister scurrying to Montréal to root out the suspected perpetrators.Footnote 9

Then, on November 1, Blair’s withdrawal from the political campaign was announced. Under the headline “BLAIR ON THE RAILWAY JOB”, the Telegraph reported: “Hon. A.G. Blair stated, before he resigned as Minister of Railways (he had resigned from that post in 1903), that he could not stand up in Parliament and attempt to steer through the Grand Trunk Pacific bill without wearing a mask and carrying a dark lantern, so great was the swindle of public money.”

But, the front-page story continued, “And it is only (now in November 1904) the sudden illness in Mr. Blair’s family that prevented him from taking the stump against this outrageous expenditure of the people’s money.” There was no other explanation. But the message was clear. Blair had withdrawn from the election campaign. He had given his final performance on the political stage.

On November 3, 1904, Laurier and his government were re-elected and the Grand Trunk Pacific deal went ahead, though it would be several years before the railway construction was completed. And, as it happened, the promoters of the CN expansion managed to beg and borrow enough financial backing to build their own transcontinental route that would link with the Intercolonial line. Canada would have not two, but three transcontinental railways, to cross its great expanse from sea to sea.

Back at the offices of the Board of Railway Commissioners, Albert C. Killam moved into the chairman’s spot on February 7, 1905.Footnote 10 He was a career jurist, although he had spent a brief time in the Manitoba legislature. Born in Nova Scotia, the son of a sea captain, he had gone to Ontario to study and practise law, and then on to Winnipeg where he had risen to the position of Chief Justice of the Court of Queen’s Bench in 1899. In 1903, he had become a justice of the Supreme Court of Canada.

With Killam in charge, politics were pushed aside while the Board turned to the pressing business at hand. In the next two years, the Commissioners made two major decisions regarding freight rates that illustrate the early acceptance of the principle of different rates according to region. In 1906, the Board allowed the use of the “mountain scale”, a higher tariff charged by CP on freight going through British Columbia. The Board had decided that the higher rate was justified because the cost of moving freight through the Rockies was greater than elsewhere. In 1907, at a Toronto hearing on international rates, the Board reduced tariffs on freight carried in Ontario and Québec in response to lower tariffs south of the border.

In 1908, the Board assumed jurisdiction over express, telephone and telegraph tolls. The Board approved tariffs and the licensing of new companies, and settled disagreements. Not only did the new duties represent confidence in the Board, but they also underscored the link between telecommunications and the railway. The telegraph system followed the railways’ rights of way and was used by the railways for signalling.

Newspapers also relied on the telegraph to transmit news. In 1910, the Board ruled that CP, which was operating a telegraph news service, was using discriminatory pricing by charging a higher price for delivering messages that originated with other news services. The Board’s ruling established a basic principle of Canadian telecommunications — the separation of control of message content from control of transmission. In the telephone industry, a similar principle was used when Bell Telephone, which had a monopoly in a large part of Canada, was prohibited from providing content-based services.

Another major area of regulation for the Board was railway safety. In 1907, the Board received a petition from the Ontario Trainmen’s Association expressing concerns about safety regulations for railway workers. The workers had reason to be concerned. In the twelve-month period ending in March 31, 1908, the death toll in railway accidents was 529 with 1,309 people injured. Among the dead were 246 employees. An alarming 806 rail workers had been injured. The Board’s Accident Branch reported that year that derailments and head-on collisions accounted for about 40 per cent of the casualties and added, “This is a state of affairs that calls for the Board’s immediate attention.”

The Board had already created the Railway Equipment and Safety Appliance Department, but the railway employees proposed a Uniform Code of Train Rules for Canadian Railways that would ensure that employees were well trained, trains were properly equipped and hazardous practices were eliminated. The Board invited railway companies and other interested parties to respond and, on July 12, 1909, the new Uniform Code was adopted.

On March 1, 1908, Chief Commissioner Killam died of pneumonia. It was a great loss to the Board as described in the Annual Report of that year: “Mr. Killam never spared himself and … he was indefatigable in his efforts to carry into effect the purposes for which this Board was created. … Mr. Killam realized that the Railway Act was ‘on trial’ and that it was well to proceed carefully and cautiously. He felt that when action was taken by the Board, there should be, as far as possible, no uncertainty in regard to the propriety and correctness of such action.”

On March 28, 1908, James Pitt Mabee, a judge from Ontario’s High Court of Justice, became the new chief commissioner, and then on July 29, the Railway Act was amended to enlarge the Board to six members from three. A new requirement stated, “Any person may be appointed chief commissioner or assistant chief commissioner who is or has been a judge of the Superior Court of Canada or of any province, or who is a barrister or advocate of at least ten years’ standing at the bar of any province.”

D’Arcy Scott, a prominent lawyer and the mayor of Ottawa, was appointed the Assistant Chief of the Board. Simon J. McLean, the political economist who had written the railway reports that had formed the basis for Blair’s bill to create the Railway Board, was another worthy appointment. The third was Thomas Greenway, who had been Premier of Manitoba from 1887 to 1900, and for a time its Agriculture Minister, and who had firsthand knowledge of the West’s attitude to railway rates. Greenway, however, was 70; he took ill upon arrival in Ottawa and died without ever sitting on the Board.

In May 19, 1909, a further amendment to the Railway Act gave the Board of Railway Commissioners jurisdiction over electric power rates. The Board, with its increasing workload and growing staff, began to lobby for larger quarters. (Since its early days, it had offices and a courtroom at 64-66 Queen Street in Ottawa.)

A Railway Grade Crossing Fund was introduced in 1909, to be administered by the Board with an annual injection of $200,000 from government, which would help provide devices like signs, lights and fencing to protect the public at railway crossings.

In the Annual Report of 1910, the Accident Branch stated: “Accidents for the period ending March 31, 1910, would be a record (low) had it not been for the unfortunate accident at Spanish River.”

A CP train travelling from Montréal to Minneapolis derailed on January 21, 1910, about 37 miles west of Sudbury, Ontario. According to the weekly newspaper, the Renfrew Mercury, “at least half a hundred human beings had been hurled to immediate death or almost immediate destruction when a train, called the Soo Express, left the rails on a straight piece of track just east of the bridge over the Spanish River.”

“The engine, tender, mail, express and baggage cars remained on the rails and the second-class car narrowly escaped going off where the rails spread.” However, the next second-class car swung around to hit the bridge and burst into flames. “Following these (cars) came the diner and the first-class car, which plunged downward into the river on the north side of the bridge. The sleeper following plunged down an embankment twenty feet high, and turned over on its side at the edge of the ice.” The death toll was reported at 42, though newspaper reports speculated that some bodies would never be recovered from the ice-bound river. Twenty people were injured.

Six weeks later, there was another dreadful accident. On March 4, a sudden avalanche killed 62 CP workers west of Rogers Pass. The workers had been clearing the tracks of snow from an earlier avalanche, according to a Vancouver Province report the next day. They were buried in snowbanks more than twenty feet high. The train’s engine, sitting on the tracks, was overturned by the impact. There were no survivors.

The Board dealt with other safety concerns. In March 1911, it issued a circular to the attorneys general of the nine provinces. “During 1911, 140 persons were killed and 69 injured while trespassing on railway property. Companies are doing their utmost to prevent this unnecessary killing … but when they prosecute … many magistrates look upon the matter as so trivial that it has been found most difficult to obtain convictions. Unless offenders are prosecuted, it will be impossible to lessen this death rate.”

In November 1911, the Board of Railway Commissioners and its staff, now numbering 63, moved to the newly constructed Grand Trunk Railway Station building at the corner of Rideau and Elgin Streets.

Meanwhile, shippers and railway companies continued to bicker about the various freight rates charged in different regions and for different commodities. Hopes were diminishing that the two new transcontinental railway companies would eliminate the imbalance in rates. The Grand Trunk and Canadian Northern were both struggling under the financial burden of their expansion projects, while Canadian Pacific, with good management, was continuing to operate at a profit.

In 1910, boards of trade in the western provinces had raised an outcry against what they called “discriminatory freight rates” and Chief Commissioner Mabee began an investigation into the rates and the so-called mountain scale. But Mabee did not get a chance to finish his task. On April 29, 1912, while presiding over a sitting of the Board in Toronto, the robust 52-year-old Chief Commissioner suffered an appendicitis attack and died on May 6.

People, airplanes and the R.100 at Saint-hubert, Québec, August 1930, CSTM/CN000246

Henry L. Drayton, a distinguished lawyer, left his job as counsel for the City of Toronto to replace Mabee on June 29. He was just 43, but already had made an impression in Canada’s legal community. Drayton quickly set to work on the freight rates case. By November 24, 1913, hearings were wrapped up and a decision was issued on April 6, 1914.

The Board found that although the higher freight rates in Western Canada might be discriminatory, they were justified by the greater competition that the railway companies faced in the eastern provinces and that the rates were, in fact, reasonable.

The Manitoba Free Press in Winnipeg ran this headline on April 8, “RAILWAY COMMISSION REFUSES WESTERN DEMAND FOR EQUALITY OF RATES WITH EASTERN CANADA” and went on to explain: “The lowest scale in the West, namely the Manitoba standard tariff, will apply to the other two Prairie provinces and the British Columbia lake section. A somewhat higher but decreased standard is to apply to the Pacific section.”

Although Manitoba was unhappy with the decision, others in the West gave it a warmer reception.

The Regina Leader-Post was full of praise: “The Board of Railway Commissioners, and particularly its chairman, Mr. H.L. Drayton, are deserving of credit for the comprehensive manner in which they have dealt with what was admittedly a complicated and difficult problem. The creation of the Railway Commission was one of the best acts of the Laurier government. It has revolutionized railway matters in Canada.”

The Calgary Herald noted “the great advantage of having a permanent Board of experts on the job.” A large photograph of the handsome Chairman Drayton was carried on the front page, with a caption that explained, “This is the man who made the decision,” as if he was particularly deserving of gratitude.

Meanwhile, the Board’s staff was dealing with other urgent matters. Fires had been a persistent hazard along the railway lines, especially in forested areas, and on January 1, 1913, the Board appointed a full-time fire inspector.

“A condition of unusually severe drought obtained during the spring and summer season of 1914,” the Annual Report for that year stated. “A total of 1,346 fires are reported as having started within 300 feet of the railway track, throughout the Dominion, during the fire season of 1914. These fires burned over a total area of 191,770 acres, of which 49,326 acres were young forest growth … and 107,496 were merchantable timber.” Of the 1,346 fires, 904 were reported to have been caused by railways. The Board issued orders to clear brush from rights of way, and to install fireguards. The Board also began to study the sparking hazards presented by certain types of coal. It suggested that oil-burning engines were less likely to emit sparks.

The Grand Trunk Pacific had completed its tracks from Prince Rupert to Winnipeg on April 7, 1914. The Canadian Northern would not finish construction of its transcontinental route until 1915. Both companies were struggling financially and made repeated pleas for government aid.

Then, as Canadians moved through the sultry days of the summer of 1914, an ominous rumble could be heard from across the Atlantic. German troops were charging through neutral Belgium in their advance on France. Great Britain issued an ultimatum for Germany to withdraw from Belgium. When the ultimatum’s deadline expired on August 4, Britain declared itself at war. Canada followed suit, and suddenly — almost overnight — the country’s domestic problems were shoved aside.

The hopes of the debt-laden grand Trunk and CN for more government support or for foreign investment evaporated with the onset of war. The War Measures Act of 1914 conferred emergency powers on the federal cabinet.

The hopes of the debt-laden Grand Trunk and CN for more government support or for foreign investment evaporated with the onset of war. The War Measures Act of 1914 conferred emergency powers on the federal cabinet. The whole machinery of government was directed to the war effort, and gradually all facets of Canadian industry and trade — from food and clothing to fuel — fell under special regulation. As the years dragged on, the cost of supporting the war took its toll and shortages developed.

The human sacrifice was tremendous as more and more soldiers signed up for service. In its Annual Reports during the war years, the Board of Railway Commissioners carried its own honour roll, listing employees who had joined the Canadian Expeditionary Forces Overseas. Canada’s workforce shrank; at the same time, industries slowed peacetime-style production, shortages developed and prices rose. Workers at home, seeing themselves at an advantage with the reduction in manpower, demanded higher wages and prices continued to climb.

In 1915, the railway companies applied for rate increases in Eastern Canada, and in 1916 the Board granted their demands. The railway companies themselves sought remedies to their financial woes. On October 23, 1917, the Canadian Railway Association for National Defence was formed, and railway companies began cooperating to avoid duplication of services and to deal with rail-car shortages.Footnote 11

As the price of the First World War mounted, the Board of Railway Commissioners granted further nationwide railway rate increases in 1917. But the western provinces and agricultural organizations appealed the decision to the government. Prime Minister Robert Borden responded by making the increase effective for only one year after the war, and by imposing a war tax on CP, which was still managing to keep its accounts in the black. The increase went into effect in March 1918.

A few months later, in July, the railway companies asked for another rate increase, this time because U.S. railway workers had won a significant increase in wages and their Canadian counterparts were threatening to strike. This time, the increase was issued by Borden’s government upon the Board’s recommendation.

The increases came too late, however, for the Grand Trunk and the Canadian Northern. Both railway companies teetered near bankruptcy. In 1915, the Grand Trunk had reneged on the deal made with Laurier over a decade earlier to take over the National Transcontinental, which had been completed on June 1, 1915, with government funds. It also offered to hand over its western subsidiary, the Grand Trunk Pacific, to the government.

In May 1916, Borden appointed a Royal Commission on Railways. He chose the Chief Commissioner Drayton from the Board of Railway Commissioners to serve on the royal commission along with W. M. Acworth, a British railway economist, and A.M. Smith, president of the New York Central Railway. Their findings were released in May 1917. Although Smith dissented, Drayton and Acworth agreed that CN, the Grand Trunk and the Grand Trunk Pacific should be united into a single national railway with other railways that the government already owned, including the Intercolonial.Footnote 12

A revised Railway Act of 1919 provided for the incorporation of the Canadian National Railways Company with a board of trustees to oversee its management. By 1923, with the addition of the Grand Trunk and Grand Trunk Pacific, the amalgamation was completed and the Canadian National Railways system was in operation.

The war alone could not be blamed for the failure of the competing railway companies. Over-building and duplication of services had crippled them with debt. The enormous growth that had been anticipated in the West at the turn of the century had not materialized. Immigration had been curtailed by the war, as had industrial development.

The war had taken a terrible toll on Canada. When peace finally arrived, the country was weighed down with enormous debt, high inflation and shortages in food and other staples. Its industries were in disarray. It had lost a large part of its workforce on Europe’s battlefields. Many of those who came home were maimed in body and spirit.

The Winnipeg General Strike, in 1919, lasted from May 15 to June 25, involved more than 30,000 workers, and resulted in a violent clash with the Royal NorthWest Mounted Police. Thirty people were injured and one died. Other strikes broke out across the country that summer.

At the Board of Railway Commissioners, changes were afoot. Chief Commissioner Drayton had been granted a knighthood for his war effort. On August 1, 1919, he left the Board to become finance minister in Borden’s government. The next day he was replaced by Frank Carvell, who had just jumped ship from his post as Public Works Minister.

The new chairman was popularly known as Fighting Frank Carvell. He had none of Drayton’s polish or charm. At 57, he was a lawyer and a politician who, after a brief excursion to the New Brunswick legislature in 1899, had resigned to run federally. He lost in the election of 1900, but won in 1904 and sat with Laurier’s government. He then broke with Laurier over the conscription issue and joined Borden. Carvell was brusque in demeanor, a legacy from his early training in the Canadian militia, and had a reputation for being outspoken and feisty. His character was perhaps not ideal for a judicial position.

The railway companies continued to seek increases to their rates. Although CP was still operating in the black, the higher cost of labour and fuel was hurting all the railway companies. When Arthur Meighen took over the government on July 20, 1920, there was an application from the railway companies for a 35 per cent advance before the Board of Railway Commissioners. But objections had been raised by shippers and regional interests.

Carvell called for a Board hearing in Ottawa for August 10. He refused requests to hold hearings around the country on the issue. An article in the Manitoba Free Press on August 6, 1920, offered some reaction to Carvell’s decision: “Curtly declining to consider the request of the Calgary board of trade for a western sitting of the Railway Commission before applications for rates increases are disposed of, and charging his telegram ‘collect,’ Hon. Frank B. Carvell, chairman of the Railway Commission, wired the Board yesterday as follows, ‘Telegram received. All principles therein set forth can be argued in Ottawa as well as in the West.’” The Free Press story continued, “His lack of courtesy, and his departure from the universal business practice of prepaying messages of this character, cause widespread comment.”

First train into the Pas-railroad employees and passengers with luggage, The Pas, Manitoba, 1908, CSTM/CN002526

Carvell wrapped up the rates hearing by August 21, and issued a judgment on August 27, raising rates between 35 and 40 per cent. Provincial, municipal and shipping representatives appealed to the government. Prime Minister Meighen asked the Board to review its decision, although he did not raise any real objections to it. Upon review, the Board restated its decision. The Board was displaying its independence and resistance to political pressure, a laudable response, but the shippers were not appeased.Footnote 13

In the spring of 1921, at the request of Cabinet, Carvell set out with Commissioner A.C. Boyce to hold hearings in Western Canada on rate equalization, that is, charging shippers the same rates no matter in what part of the country they did business or what commodity they shipped. The hearings that followed revealed just how impossible an equalization scheme would be in a country with so many diverse regional interests. It was becoming painfully obvious that there would be no satisfactory solution, within the Board’s regulatory powers, to the divergent regional interests and the profit objectives of the railway companies. Carvell, for his part, made some public speeches defending previous Board decisions, and was criticized for expressing his opinions so openly. He was straying from the impartiality required in his position.Footnote 14

The governments of Arthur Meighen and his successor, William Lyon Mackenzie King, continued to grapple with the equalization of freight rates. At the same time, the Canadian economy entered a downturn that lasted into the mid-1920s. The railway companies reduced some rates of their own accord and the railway commission lowered some more.

In 1922, the government appointed a special committee to study the Crowsnest Pass Agreement of 1897, in which CP had agreed to certain rate reductions. The committee restored some parts of the original Crow agreement — which had been lifted during the war — to reduce rates for shippers.Footnote 15

In 1923 the Board, at the request of cabinet, reduced railway rates on grain exports from Vancouver.

On August 9, 1924, Frank Carvell died amid a clamour for an investigation of the Crow rate.

Prime Minister Mackenzie King appointed Harrison A. McKeown, the chief justice of New Brunswick’s Supreme Court, to replace Carvell. McKeown had served in the New Brunswick legislature as Solicitor General and Attorney General. In 1908, he was appointed a justice of the province’s Supreme Court and later Chief Justice. He had also taught law, and had been dean of the law faculty at the University of New Brunswick from 1922 to 1924. McKeown was 61 when he joined the Board and he soon found problems of his own.

In October, after a seven-day hearing, the Board decided to help railway companies by dispensing with the Crowsnest Pass Agreement, despite the 1922 statute that had reinstated the relatively low Crow rate on grain.

An appeal to the Supreme Court by the western provinces resulted in a ruling in 1925 that the Board could not drop the Crow rate. Railway companies could, however, use the narrow interpretation of the agreement as set in 1897. In response, King’s government stepped in to cancel the Crow-based rates, except those on grain and flour. Parliament also ordered the Board to hold a general inquiry into other rate issues.Footnote 16

On September 2, McKeown and Commissioner Frank Oliver, a Westerner who had founded the Edmonton Bulletin, approved fixing the grain rates to Vancouver based on the Crow rate. They did this despite the opposition of three other Board members, who had made a decision on the same issue in 1923. Simon J. McLean, who had been with the Board for 17 years, A.C. Boyce and Calvin Lawrence, were concerned, in fact, by the lack of impartiality in McKeown’s decision. McLean summed up their objection “that fairness and reasonableness of the rate is to be determined on the facts after due enquiry; that the order was issued on a record partially heard and incomplete.”Footnote 17

A new method of answering the needs of the shippers and the railway companies was found in the Maritime Freight Rates Act that was adopted in 1927. The Act reduced by 20 per cent the local tariffs and rates on freight originating in the Maritimes and bound for other parts of Canada. The Act also allowed for the compensation of railway companies for any losses resulting from the reductions. The Board was given the task of determining the annual compensation for the railway companies.

A new method of answering the needs of the shippers and the railway companies was found in the Maritime Freight Rates Act that was adopted in 1927. The Act reduced by 20 per cent the local tariffs and rates on freight originating in the Maritimes and bound for other parts of Canada. The Act also allowed for the compensation of railway companies for any losses resulting from the reductions. The Board was given the task of determining the annual compensation for the railway companies.

Also in 1927, the Railway Board issued a decision in the General Rates Investigation by which it maintained the higher mountain tariff and transcontinental rates to interior points; it also ordered a lower rate on grain over the Canadian National route from the West to Québec City, and required railway companies to adopt a more liberal interpretation of the 1925 grain legislation.

In 1929, approval of tolls for international bridges and tunnels was added to the Board’s jurisdiction.

In the Annual Report for that year, the Board stated that the fire season was one of the worst seen in 40 years in the Prairie provinces. What the report described as a “long period of extreme drought and high winds in the West” resulted in a poor grain crop that fall.

There was more bad news to come. At the end of October, the Wall Street stock market suffered a drastic fall in values. On the same day, the Winnipeg Grain Exchange was hit by falling prices. The Great Depression had arrived. Hundreds of thousands of Canadians were unemployed, some starved, others lost their homes, and families were broken apart.

The government looked for ways to offer assistance. By 1933, more than a million Canadians were on government-funded relief. Make-work projects were established to give jobs to the unemployed. Among the projects were several supported by the Railway Grade Crossing Fund. From 1930 to 1938, the government increased its financial allotment to the Fund, which had been administered by the Board since 1909, to contribute to safety improvements at highway crossings, now with the added objective of providing work.

Railway companies also made use of government relief funds to clear the railway rights of way. A huge clearing effort in 1936 led to this report from the Board’s fire inspector: “During the season of 1936 the railways … carried out a large amount of right-of-way clearing with special gangs recruited from the ranks of the unemployed who had heretofore been domiciled in labour camps throughout the country. This work will have beneficial results in greatly reducing the fire hazard.”

The next year, the fire inspector reported, “A minimum of major clearing of rights of way was carried on during 1937. Work in the previous year accounted for 1,700 miles, on both sides of the tracks.” To no one’s surprise, the number of fires along railway lines was greatly reduced that year.

Meanwhile, McKeown retired on March 1, 1931, as chief of the Railway Board. Charles P. Fullerton, a justice of the Manitoba Court of Appeal, was appointed on August 13, 1931 to replace him.

In November, in the depth of the Great Depression, R.B. Bennett’s government appointed a royal commission to look into the condition of Canada’s transportation system. Mr. Justice Lyman Duff, of the Supreme Court of Canada, was named head of the commission. The CN system was suffering financially and the government sought a solution to the public railway’s problems.Footnote 18

In 1932, Sir Henry Thornton resigned as head of CN, a position he had held for close to ten years, amid rumours of lavish spending. The next year, the government set up a three-member board of trustees to govern CN, and asked the 64-year-old Fullerton to head the board.Footnote 19

At the same time, the government adopted the Canadian National-Canadian Pacific Act of 1933 to encourage cooperation and coordination of the railway system. In the coming years, the two railway companies, crippled by the economic standstill and loss of customers, would agree to pool certain passenger services, and eliminate unprofitable duplication of services.

In 1933, the Board of Railway Commissioners assumed jurisdiction over the abandonment of rail lines, in which they were given discretion to weigh the railway companies’ financial responsibilities against the users’ transportation needs.

During 1934 and the first half of 1935, no chief was appointed to the Railway Board, and the position was temporarily filled by Assistant Chief Commissioner Simon J. McLean, who had been one of the original designers of the Board, and now had served on it for more than 25 years.

On August 12, 1935, Hugh Guthrie was appointed as Chief Commissioner by Prime Minister R.B. Bennett. A lawyer from Guelph, Ontario, Guthrie had a long career in politics, entering the House of Commons in 1900. Guthrie was 69 years old, and the Board had entered its fourth decade.

Railways were no longer the only means of transporting freight or passengers across the country. Road construction — including major projects like the Trans-Canada Highway — and technological advances were making motor vehicles a viable source of competition.

The civilian aviation industry had also been developing in Canada since World War I. Bush-flying had long been an accepted method of carrying passengers and goods to areas of Canada’s North where no other transportation was available. By the mid-1930s air travel was becoming more common with several small airline companies operating in Canada.

In 1935, a plan for a national airline was being considered by Bennett’s government. However, a fall election brought William Lyon Mackenzie King to power as prime minister, and the transportation portfolio was then entrusted to Clarence Decatur Howe.

Howe had been born in the United States and trained as an engineer. In Canada, he had made a successful business of building grain elevators. As the Minister of Railways, Howe disbanded the board of trustees that had been overseeing CN, and dismissed Fullerton, the former Chief of the Board of Railway Commissioners.

Then he set about reforming Canada’s transportation system. The Transport Act of 1936 created the first federal Department of Transport with Howe at its helm. The department consolidated the functions of three departments: Railways and Canals, the Civil Aviation section which had been under the umbrella of National Defence, and the Marine Department.

In 1938, the Transport Act was passed, creating the Board of Transport Commissioners from the old Board of Railway Commissioners.

The era of railway supremacy had ended. It was time to move on.

Symbolic of that change were two retirements announced in the final Annual Report of the Board of Railway Commissioners: Simon J. McLean, who had written the reports at the turn of the century that had assisted A.G. Blair in designing the Railway Act of 1903, retired as Assistant Chief Commissioner to become a technical adviser. And A.G. Blair Jr., the son of the founder and first chairman of the Board, retired as legal counsel on November 28, 1938. He had been with the Board since 1904.

Engines of Change

The Board of Transportation Commissioners, 1938 to 1967

- July 1, 1942, Canadian Pacific Air Lines started operations.

- August 1950, railway unions held the first nationwide strike in Canada—legislation was passed to send the strikers back to work after nine days.

As Canada approached its 71st birthday in the spring of 1938, newspapers delivered daily reports of the latest skirmishes in Spain’s civil war and of the growing menace of fascism as Adolf Hitler’s shadow crept ominously across Europe.

At home, the national economy was shaking off the lethargy that had gripped it for almost a decade in the Great Depression.

On May 17, the Canadian Press reported that “more than 585,000 motor vehicle licences have been taken out in Ontario this year, 61,000 more than in the same period last year.”

A few days later, the Ottawa Citizen reported that “three days ahead of schedule, the Dibblee Construction Company started work this morning on grading Uplands Airport for Trans-Canada Air Lines, preparatory to laying two runways. …Work on the airport is being rushed so that the runways will be ready by June.”

A TCA Canadair DC-4M North Star flying over Kinley Airport, Bermuda, 1950, CSTM/CN000261

On July 2, the Citizen reported that the federal cabinet was still working, although Parliament had been prorogued the day before, on the Dominion holiday. “Governor General Lord Tweedsmuir was on hand for the prorogation ceremony at midnight Thursday night (June 30) but when it was found impossible to wind up business by that time, Prime Minister Mackenzie King advised him not to postpone his vacation trip to England… Mr. Justice Cannon, acting as deputy to the Governor General, prorogued the session at 3:40 p.m. (on July 1).”

The House had been occupied with the passage of several bills in its last days before the summer break. One of the bills passed was the Transport Act, which created the Board of Transport Commissioners with authority over inland waterways and airlines, along with jurisdiction over railways, telegraphs, telephones, and express companies, inherited from its predecessor, the Board of Railway Commissioners.

The press made little mention, during those formative days, of the man who had directed the Board’s creation. But for the next 19 years of its existence, the Board of Transport Commissioners would constantly be aware of C.D. Howe’s presence and of his power over transportation policy.

Howe was 49 years old in 1935 when he won the Port Arthur riding in Northwestern Ontario. Mackenzie King, recognizing him as a shrewd, tough-minded businessman, pulled him into his new cabinet.Footnote 20

By 1938, as the Minister of Transport, Howe had made major policy changes to the transportation industry. He had no patience, however, for the political life and he made no bones about it. A typical remark was: “I do not think I’m doing anything useful when I sit in the House and listen to the kind of blather that’s being talked here.”Footnote 21

Despite his shortcomings in diplomacy, Howe was one of Mackenzie King’s most successful cabinet ministers. In 1937, he had spearheaded the organization of operating and ground services for Canada’s first transcontinental air system. He then oversaw the creation of Trans-Canada Air Lines, the country’s first publicly owned airline, as a subsidiary of the publicly owned CN, and with a monopoly over the international and transcontinental routes, and over airmail service. Throughout his political career, TCA would remain Howe’s favourite project.

According to the Transport Act, the Board was given authority over air and water transport, but its powers over these two modes were much more limited in scope than over railways. For instance, with inland water transportation, the Board had jurisdiction over licensing and rates, but not over other matters. In the aviation sector, the Board had power of approval for licensing and rates for air service between specified points in Canada, or between specified points in Canada and outside, but the actual points and places of its jurisdiction would be determined by cabinet.

The Transport Act also gave the Board the power to approve agreed-upon charges between carriers and shippers. This section of the Act allowed the heavily regulated railway companies to compete in specific areas with the unregulated truckers, for instance, by making agreements for special rates with large-volume shippers for a minimum quantity of freight.

The new Board continued with the same commissioners who had been appointed to the previous Board, and with the same staff.

The Annual Report of 1939 describes the added workload: “A great deal of correspondence, discussion and detailed work has been necessary in respect to the licensing provisions of the Transport Act, particularly so in respect to aviation,” wrote W.E. Campbell, director of the Traffic Department. “A large amount of educational work has been necessary in the preparation and the filing of tariffs; also, it has been necessary to investigate alleged violations of licences, tariffs, etc., much of which might have been avoided had there not been such an extraordinary lack of cooperation among the various companies, and a greater appreciation of the necessity to comply with the principles laid down in the Act.”

The Annual Report made no mention of the cataclysmic events of the late summer of 1939 that would take Canada into another world war. For several years, tensions had been building in Europe as Germany’s Hitler led a campaign of aggression against neighbouring countries. In 1938, there were plans afoot for a British Commonwealth Air Training program to be set up in Canada. When Hitler invaded Poland in the fall of 1939, there was no turning back. On September 10, 1939, Canada declared war on Germany.

In the 1940 Annual Report, Chief Engineer D.G. Kilburn wrote that besides the normal work of the department, “war conditions have imposed additional duties. Many new industrial war plants and air fields have been constructed and existing plants enlarged. The consequent increased traffic on the railways brought about additions to existing railway track facilities and, to meet growing war-time demands for railway transportation services, further additions are under consideration. These increased facilities involve examination, inspection and approval.”

World War II created a boom in Canada’s transportation industry. By the second year of the war, CN reported revenues of over $300 million and, for the first time in many years, it was not dependent on the public purse.Footnote 22

Meanwhile, the approval of freight rates was removed from the Board’s jurisdiction during the war. As noted in the Annual Report of 1941, “Order in Council P.C. 8527 of November 1, 1941, imposed restrictions upon the rates charged for transportation and communication services. The facilities of this department are being utilized to assist the Wartime Prices and Trade Board in carrying out the provisions of the Order in Council.” The government froze prices and wages to the level prevailing between September and October 1941.

As the Board reiterated in later war-time reports, “There can be no increase in any rates or charges for transportation of goods or passengers […] without the concurrence of the Wartime Prices and Trade Board.”

Meanwhile, the Board carried on with its regular duties of issuing licenses, approving abandonment and construction of railway lines, administering the Railway Grade Crossing Fund, and investigating railway accidents and fires.

On November 3, 1939, Hugh Guthrie, the Board’s chief commissioner, died at the age of 73. Guthrie’s successor was Colonel James Albert Cross who had been Saskatchewan’s attorney general from 1922 to 1927, under two premiers. In World War I, he had served as an officer with the 28th Battalion and had been made a companion of the Distinguished Service Order.

On April 1, 1940, the Ottawa Journal described Cross as “a modest soldier-lawyer, who once was elected to the Saskatchewan legislature without making a single speech” and “at 63, he looks a good ten years younger.”

On April 9, C.D. Howe became Minister of Munitions and Supply, a department specifically created to give the government control over industry during the war years. He also kept the post of Minister of Transport.

Throughout his career, Howe maintained a protective interest in Trans-Canada Air Lines (TCA). He considered the airline his own creation, and watched closely any Board decisions that affected the air industry. (In fact as late as June 20, 1950, when Howe was Minister of Trade, Opposition Leader George Drew passed a motion in the House of Commons to have jurisdiction over TCA turned over to the Transport Minister, and out of Howe’s control. The motion was voted down.)

The Board’s role in aviation was unclear from the first. The Transport Act stipulated that the Board had jurisdiction over points and places that were specifically named by cabinet. In several instances, when the Board made a decision regarding an air licence, the cabinet overruled the Board by “unnaming” the route, and thus removing it from the Board’s jurisdiction.

The Board’s role in aviation was unclear from the first. The Transport Act stipulated that the Board had jurisdiction over points and places that were specifically named by cabinet. In several instances, when the Board made a decision regarding an air licence, the cabinet overruled the Board by “unnaming” the route, and thus removing it from the Board’s jurisdiction. Also, if the Board turned down a licence for an air operator to fly to a place which had been named by cabinet, the ruling could be circumvented by the air operator flying to an “unnamed” place near the named place.Footnote 23

Soon after TCA was created, Canadian Pacific Railways, which briefly had been included in a proposal to create the national airline, decided to create its own air service. On July 1, 1942, Canadian Pacific Air Lines started operations. It had bought up several air routes from smaller operations, and with Board approval had air licences that expanded its territory into several markets.

One of its purchases was an air company that flew between Victoria and Vancouver. At the time, TCA did not fly between the two cities because there was not a proper landing site at Victoria for its larger planes. But when an airport was built that TCA could use, it applied to the Board of Transport Commissioners for a licence to deliver mail and provide passenger service to Victoria.

The Board was faced with a difficult decision that would, on the one hand allow the duplication of services, and on the other hand block the publicly owned TCA from fulfilling its transcontinental mandate. The Board ruled that TCA could deliver mail between Vancouver and Victoria and also that it could provide air passenger service, but only as a continuation of its transcontinental route. That left the local passenger service, which represented the majority of the traffic, to Canadian Pacific Air Lines.Footnote 24

A TCA crew aboard a Canadair DC-4M North Star, 1950, CSTM/CN000256

In the House of Commons, on June 11, 1944, Howe expressed his opinion of the Board’s performance: “The Board of Transport Commissioners is bound by the Transport Act and is concerned chiefly with railway problems. The effect of the administration of the Board was this. In 1938, when the Act was passed, there were a great number of independent air operations in this country. Four years later, there was only one independent air operation. Every other air operation in the Dominion was owned and operated by the railway companies.” Canadian Pacific, under Board approval, had bought more than 40 air operations in those years. Howe was concerned that the private railway company had been allowed to purchase such a large share of the domestic air services.

On the matter of the Victoria-Vancouver route, Howe said: “The Board ruled that Trans-Canada Air Lines must operate from Vancouver to Victoria with empty seats, because there was another air operation connecting the two centres. The fact that the other operation was overcrowded and could not begin to handle the traffic, and could not obtain planes sufficient to carry the traffic did not weigh with the Board.”

On September 11, 1944, the Transport Act was amended to provide for “the removal of commercial air services from the jurisdiction of the Board of Transport Commissioners.”

The Aeronautics Act, at the same time, created a new Air Transport Board to provide licensing and regulatory functions. In the House of Commons, Howe explained the new Aeronautics Act: “A much more scientific as well as a fairer method, a method more in keeping with the supremacy of Parliament is being adopted.”

Mackenzie King had made an earlier policy statement about the airline industry. “Competition between air services over the same route will not be permitted,” he had baldly stated in the House of Commons on April 2, 1943. And although he had added that there would be areas where private enterprise would participate, Mackenzie King made it clear that the government’s air policy was to effect for Canada “a freedom of action in international relations because it was not limited by the existence of private interests in international air services.” At the end of World War II, the government wanted to control the air industry and ensure its development, avoiding the problems the railway industry had suffered at the hands of private enterprise.

The Air Transport Board’s role was clearly laid out in the Act as an administrative body, subject to close ministerial control. The Air Transport Board could issue licences and regulations, but only subject to the approval of the Minister of Transport. Also, the Air Transport Board was responsible for recommending policy changes to the Minister. In effect, it had none of the independence of the Board of Transport Commissioners.

Another policy change introduced by C.D. Howe involved ownership of the airlines by the railway companies. On March 17, 1944, Howe stated: “It is becoming obvious that ownership of airways by our competing railway systems implies extension of railway competition into transport by air, regardless of the government’s desire to avoid competition between air services. The government has decided that railway companies shall not exercise any monopoly of air services. Steps will be taken to require our railway companies to divest themselves of ownership of airlines to the end that, within a period of one year from the ending of the European war, transport by air will be entirely separate from surface transportation.”

The effect of requiring CP to divest itself of the Canadian Pacific Air Lines would be considerable expense and time spent on the reorganization. As was apparent in this and other policy statements, Howe was determined to advance the cause of the publicly owned Trans-Canada Air Lines at the expense of private enterprise. (The divestiture policy was reversed, however, in 1946 and CP was allowed to keep its airline.)

The first chairman of the Air Transport Board was R.A.C. Henry, who had worked for CN and had been deputy minister of Railways and Canals in 1929 to 1930. In 1940, he had assisted in the development of the Department of Munitions and Supply. The two other members were Air Vice Marshall Alan Ferrier of the Royal Canadian Air Force, an aeronautical engineer, and J.P.R. (Roméo) Vachon, a pioneer in the Canadian aviation industry with experience in both flying and aeronautical engineering.

In future years, many of the members appointed to the Air Transport Board were drawn from the civil service. This practice reinforced the already close relationship between the Board and government.Footnote 25

The Air Transport Board was not required to submit its own Annual Reports, another indication of its lack of autonomy. However, it did issue one report for the period between September 11, 1944 and December 31, 1946. That document was directed to the Minister of Reconstruction and Supply, a new position created for C.D. Howe in late 1944.

That Air Transport Board Annual Report, which was published in 1947, clearly advanced the government’s thinking: “In accordance with laid down policy, direct competition is not permitted on scheduled air routes. The reason is that, at the present stage in the development of air transportation in Canada, the volume of traffic is such that there is not room for competing services and it is considered uneconomical to try to divide the small available business between two or more carriers. While at some later date a policy of competition might be justified, at the present time it would be disastrous and is considered to be against the public interest.”

As Minister of Reconstruction, Howe had a mandate to direct the post-war reorganization of industries and manpower. He still held the portfolio for Munitions and Supply, and was on his way to earning the sobriquet “Minister of Everything.”

Howe was also still in a position to direct transportation policy after the war. The Board of Transport Commissioners’ Annual Report, covering the period of 1945, stated: “During the year, the Board of Transport Commissioners was asked by the Department of Reconstruction to make a survey of possible railway crossing eliminations at certain priority points throughout Canada, having in mind public convenience and necessity, together with possible post-war employment.”

A Bureau of Transportation Economics was created in 1946 to provide economic and statistical studies for both the Board of Transport Commissioners and the Air Transport Board.

Wage and price controls were dropped at the end of the war, and soon a clamour for higher wages was heard. In 1946, both the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific railway companies raised their wages in response to union agitation.Footnote 26

Inevitably, the Railway Association of Canada, representing CN and CP, applied for a general increase in freight rates to offset the increased operating costs and declining volume of post-war traffic. After 150 days of hearings, the Board rejected the railway companies’ application for a 30 per cent increase.

On March 30, 1948, the Board settled on an increase of 21 per cent, using a cost-revenue methodology. Seven of the nine provinces (not Ontario or Québec) appealed the decision to cabinet, claiming that the Board had lost the public’s confidence by its methodology. While the government reviewed the decision, it asked the Board on April 7, 1948, to conduct a general freight rates investigation. Meanwhile, the Railway Association sought another 20 per cent increase from the Board.Footnote 27

On June 30, 1948, Chief Commissioner Cross, now 72, in poor health and worn down by the contentious freight rates issue, resigned. There was nothing in the local papers on July 1, 1948, about Cross’s resignation — or about his replacement, Justice Maynard Brown Archibald. The big news on that day was Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s announcement in the House of Commons that he would be retiring.

Justice Archibald had been appointed to the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia in 1937, and was appointed to the Exchequer Court of Canada on the same day that he was appointed to the Board of Transport Commissioners. The Board’s Annual Report for 1948 explained that an amendment to the Railway Act that year provided that the Chief of the Board of Transport Commissioners would be a judge of the Exchequer Court (now the Federal Court).

Meanwhile, the Board continued to hear the Railway Association’s second request for a freight rate increase. The Board decided to give an interim increase of 8 per cent on July 27, 1948. CP appealed to the Supreme Court and the Court ruled that the Board should make a final decision.

In October 1948, the government rejected the appeal by the provinces in what came to be known as the 21 per cent case, the rate increase originally approved by the Board in March 1948, and asked the Board to review its decision. The government also decided to set up a royal commission to study transportation. In January 1949, W.F.A. Turgeon, formerly a judge in Saskatchewan, was appointed to head a royal commission that would study freight rates and transportation policy.

In October 1948, the government rejected the appeal by the provinces in what came to be known as the 21 per cent case, the rate increase originally approved by the Board in March 1948, and asked the Board to review its decision. The government also decided to set up a royal commission to study transportation. In January 1949, W.F.A. Turgeon, formerly a judge in Saskatchewan, was appointed to head a royal commission that would study freight rates and transportation policy.

And the Board, following the Supreme Court order, authorized a freight-rate increase of 16 per cent, but again the Railway Association returned, claiming that the Board had miscalculated the shortfalls. The Board’s final decision was a 20 per cent increase announced on July 27, 1949.

In 1948, the Board had also dropped the mountain scale (established in 1914 as a higher railway rate for traffic in the Rockies) in response to an application from British Columbia.

It was a tumultuous time for the railway companies and by extension for the Board of Transport Commissioners. The combination of fierce competition from trucking and air operations exacerbated by higher operating costs was putting extreme pressure on railway companies, which were already shackled by stiff regulations.

Meanwhile, the shipping industry had experienced a huge burst of expansion in the war years, most of it created by the federal government. In 1947, in an effort to stem the post-war decline in the industry, the government created the Canadian Maritime Commission. The Commission’s responsibilities included administering subsidies and recommending policies to the Minister of Transport.

The Board of Transport Commissioners continued to approve licences and rates for inland water transport, and still had jurisdiction over telegraph, telephone and express companies. In 1949, it was given jurisdiction over licensing of oil and gas pipelines. But the majority of the Board’s workload remained railway regulation.

In August 1950, railway unions seeking higher wages and better benefits held a nationwide strike, the first in Canadian history. Legislation was passed to send the strikers back to work after nine days. The government appointed Mr. Justice R.L. Kellock, of the Supreme Court of Canada, as an arbitrator to settle the dispute. After hearing both sides, Kellock granted a wage increase and directed that a 40-hour, five-day week should be instituted as of June 1, 1951. This ultimately would put more pressure on the railway companies to increase their rates.Footnote 28

The Board of Transport Commissioners, meanwhile, was the target of criticism from various quarters for its handling of the railway problems. A particularly scathing attack against the Board was delivered in the House of Commons on June 21, 1950, by Opposition Leader George Drew. At this point, the same party had remained in power in Ottawa for 15 consecutive years and Louis St. Laurent had been the prime minister for two of those years.

Drew began with a denunciation of the Board of Transport Commissioners, saying that “it had demonstrated itself to be incompetent by its own actions during this extended period (of freight rate hearings).” Then he launched into a long diatribe liberally laced with the word “incompetent”, and recommended that the Board be disbanded and that a new board be created. In response to the criticism, it was noted in the House that Justice Archibald, the Board’s Chief Commissioner, was “gravely ill.”

The report from the Turgeon Royal Commission was tabled in the House of Commons on March 15, 1951. It recommended an equalization of freight rates; that the Board of Transport Commissioners establish a uniform system of classification of rates throughout Canada, excluding the Maritimes; that the Board establish a uniform system of accounts and reports for the railway companies; and that the lower rates on grain and flour as set out in the Crowsnest Pass Agreement of 1897 continue. It also recommended that the Board deal with applications at a speedier rate.

On October 30, 1951, Transport Minister Lionel Chevrier dealt with more criticism about the Board of Transport Commissioners. The resignation of the 60-year-old Justice Archibald was set for the next day, and Opposition members took the opportunity to attack the Board again. In defending the Board’s members, Chevrier blamed the problems on staff shortages.

“The Board is lacking in expert staff. That is a fact,” Chevrier told the House of Commons. “The Board has not the required traffic advisers that it should have. … Traffic experts are almost impossible to find in this country.”

The new Chief Commissioner was John D. Kearney, a lawyer and career diplomat.Footnote 29 He had held several foreign posts that had earned him a reputation as an incisive and astute arbitrator. He had headed the Canadian mission in Dublin from 1941 to 1945, and, in 1947, became the first Canadian High Commissioner to India after that country achieved independence. Kearney’s appointment to the Board coincided with his appointment as a Justice of the Exchequer Court of Canada. An amendment to the Railway Act in 1952 would make the appointment of Chief Commissioner an automatic appointment to the Court of the Exchequer.

In January 1952, the Board began hearings on rate equalization. After a long series of consultations, equalization on class rates finally went into effect in March 1955.

A new department of Accounts and Cost Finding was set up by the Board to handle the uniform classification of rates and associated accounting systems.

While the Board continued to deal with freight-rate applications, other issues were brewing.

In 1949, Newfoundland joined Confederation. The new province’s railways became part of the CN system, and eventually decisions about the province’s freight rates and other railway issues fell within the Board’s jurisdiction.

In 1955, the Railway Act was amended to increase Parliament’s annual appropriation of funds to the Railway Grade Crossing Fund to $5 million. The amendment was based on a report submitted on May 10, 1954, after the Board carried out a Canada-wide investigation of railway-highway crossing problems.

An amendment to the Transport Act in 1955 removed the necessity of the Board’s approval for agreed charges. The amendment gave greater freedom to carriers to make specific agreements on charges, the only requirement being that the charges be filed with the Board 20 days prior to their taking effect.

Victoria Inner Harbour looking Southeast, British Columbia, 1947,

Photographer: W. Atkins, CSTM/CN000238